As always, please ‘like’ this post via the heart below and restack it on notes if you get something out of it. It’s the best way to help others find my work. Of course, the very best way to support my work is with a paid subscription.

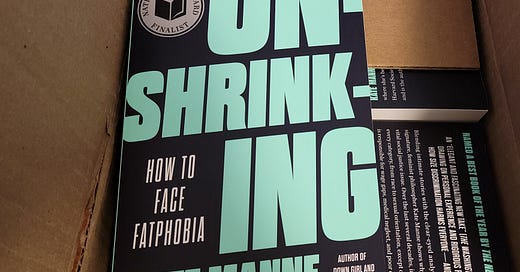

I won’t lie. Releasing Unshrinking: How to Face Fatphobia in the height of the Ozempic craze last year was a huge uphill …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to More to Hate to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.